7/28/2021

When I was a child, I read a biography of Marie Curie, who grew up in Poland, then part of the Russian Empire. Every day, when she and her sister walked to school, they made a point of spitting on a statue of a hated Russian leader, whose name I cannot recall.

When I was a child, I read a biography of Marie Curie, who grew up in Poland, then part of the Russian Empire. Every day, when she and her sister walked to school, they made a point of spitting on a statue of a hated Russian leader, whose name I cannot recall.

I thought about Curie when, earlier this month, the city of Charlottesville, Virginia, removed statues of Confederate generals “Stonewall” Jackson and Robert E. Lee. I recalled, as well, my visit to the Ukraine a few years ago. In Yalta, my husband and I rested at a picnic table near the harbor, where we watched children race around on skateboards. A few yards away was a statue of Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin. Why on earth was it still there, we wondered, thinking of how the people of Iraq, with some assistance from U.S. troops, destroyed a huge statue of Saddam Hussein. A tour guide told us that the statue acknowledges that Russia’s actions in Ukraine is part of the country’s history, unpleasant as it is. Second, she said, the statue was, unlike many other statues of Lenin, of rather good quality.

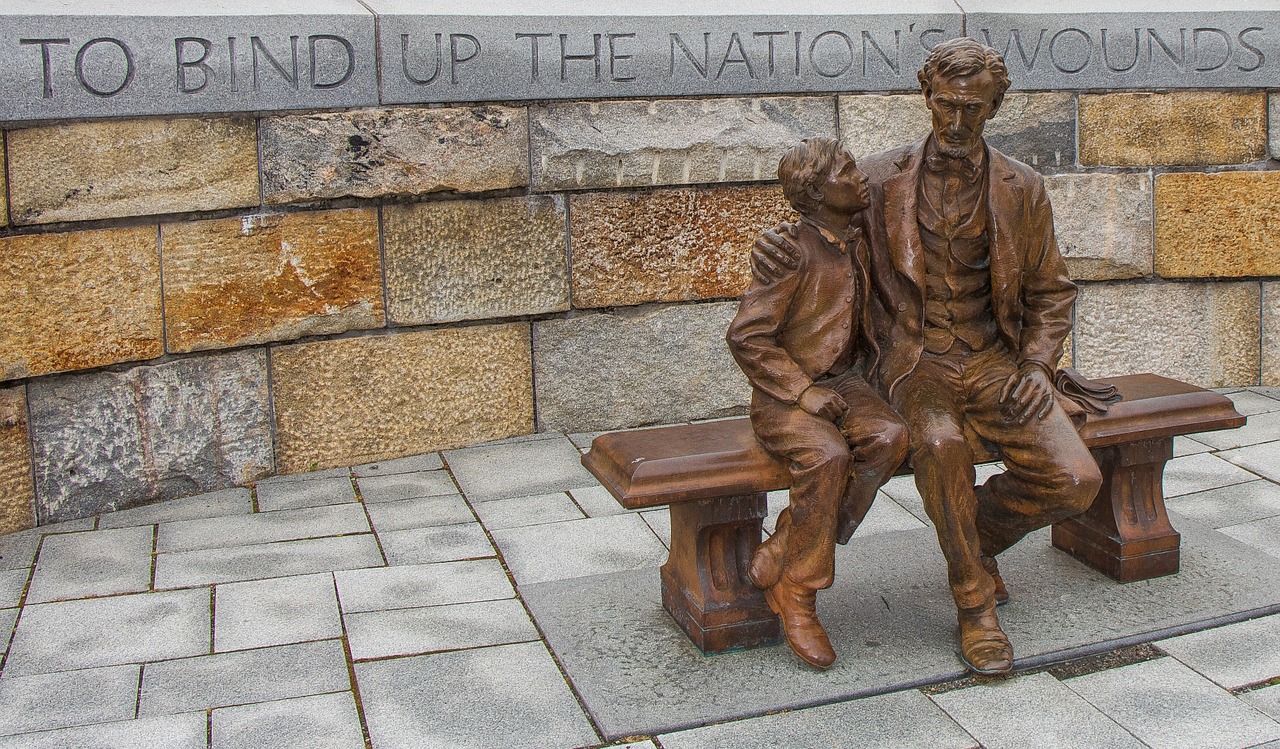

I understand the anger of Americans to whom statues of Confederate heroes are a reminder of what these men were fighting for: Slavery. But I think rather too many statues have been destroyed in recent months, including those of Abraham Lincoln in Portland, Oregon (who led a war to end slavery and keep the Union intact) and Theodore Roosevelt (the first president to invite an African American–educator Booker T. Washington–to dine with him at the White House). Knocking them down seems like the statuary equivalent of book burning.

Those who want to keep controversial statues say they are meant to teach us about historical events. Their opponents reject this argument on the grounds that Americans can learn about history through books and schools and museums. But can we? In recent decades we have seen school history books devote more space to Marilyn Monroe than George Washington, while parents and school districts are currently fighting ferociously over Critical Race Theory, with both sides determined to control the historical narrative.

As for museums, in 1995, the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum fought a battle royale with members of the public over how the Enola Gay, a B-29 Superfortress bomber from which the first atomic bomb was dropped on the citizens of Japan in 1945, should be portrayed. Should it be celebrated as part of an event that ended a horrific war, thus saving many lives on both side—or condemned as an instrument of death that ultimately took the lives of some 200,000 Japanese? Both sides thought the other was attempting to distort historical truth.

And at the National Museum of African American History, African American Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas was omitted, as was Janice Rogers Brown, the first African American woman to serve on the California Supreme Court, as well as the U.S. Circuit of Appeals in Washington, DC. Conservative blacks, it seems, need not apply to this museum. School children visiting the museum certainly won’t learn about them.

We can’t always count on finding the whole truth in books, either. In recent years, Amazon has stopped selling books about reparative therapies and accounts by people who were healed of their same-sex attraction, because outspoken members of the LGBT community, wanting to control the narrative, demanded the company do so. This act of censorship will make it difficult for future authors to write and sell their books on this subject, or on other controversial issues, for that matter, because if publishers know they can’t sell your book on Amazon, they’re not likely to bother publishing it.

As with the statue of Lenin in the Ukraine, the statues of Confederate leaders represent a segment of our history. To many descendants of Confederate soldiers, the statues honor ancestors who fought hard for what they believed in, however erroneous those beliefs were–and one hopes their descendants no longer believe chattel slavery was or ever is acceptable. Others—and I do not blame them–look at these statues see only representatives and reminders of slavery.

So what is the answer?

In a country as diverse as ours, it’s inevitable that not everyone will like every statue. And we should acknowledge that even the greatest men and women have their flaws. For instance, sordid revelations have come out in recent years about civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. Should we destroy statues to his memory?

Instead of tearing down statues some of us disapprove of, let’s add statues that provide dimension to the historical narrative. For instance, in Richmond, Virginia, the former Confederate capital, a statue of African American tennis great Arthur Ashe was raised on Monument Avenue in 1996, where he kept company with five Confederate heroes (which were removed in 2020 during the unrest following the killing of African American George Floyd, including the statue of Jefferson Davis, which was torn down by a mob).

In recent years, we have seen statues erected to the memory of Frederick Douglass (College Park, Maryland, 2015), Rosa Parks (Washington, DC, 2013), and Harriet Tubman (Manhattan, NY, 2007). In 2018, the National Memorial to Peace and Justice erected statues in Montgomery, Alabama, in memory of the victims of lynching. Good, good, and good.

America’s founders are honored for many things, but not, unfortunately, for women’s suffrage. Should we tear them down because of their views on this matter? Of course not. We should, instead, celebrate those who fought for female suffrage, as New Yorkers did when they unveiled a statue of Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Sojourner Truth, whose work brought us closer to giving women the right to vote.

In 2014, the Victims of Communism Memorial Statue was dedicated in Washington, DC in memory of the 100 million people victimized by communism. This statue surely didn’t please left-wing college faculty members who have never lost their love of communism, but that’s just too bad.

And that should be our answer to those who want to remove, sometimes by force, statues of people they don’t like. Statues can teach about the worst parts of our history, as well as the best—but not in towns that tear them down.